Public Rails vs Private Ledgers

An institutional decision framework

Over the past decade, many of us have watched a familiar pattern play out.

A new “enterprise blockchain” arrives, promising privacy, control, and regulatory comfort. A consortium forms. Large financial institutions sign MOUs. Impressive proofs-of-concept, some live deployments, and then… stagnation.

Was this because the technology was bad? Or because the permissioned consortium model has structural limits that even the best implementation cannot escape?

We use Canton as our reference point, not because it failed, but because it has gained real traction. Canton represents one of the most technically ambitious permissioned platforms to date, backed by tier-one institutions and some initial production deployments. If we want to understand the category’s limits, we should examine one of its strongest examples.

What follows is a decision framework for institutions choosing between:

- Private ledgers with trust-based privacy, and

- Public blockchains with cryptographic privacy.

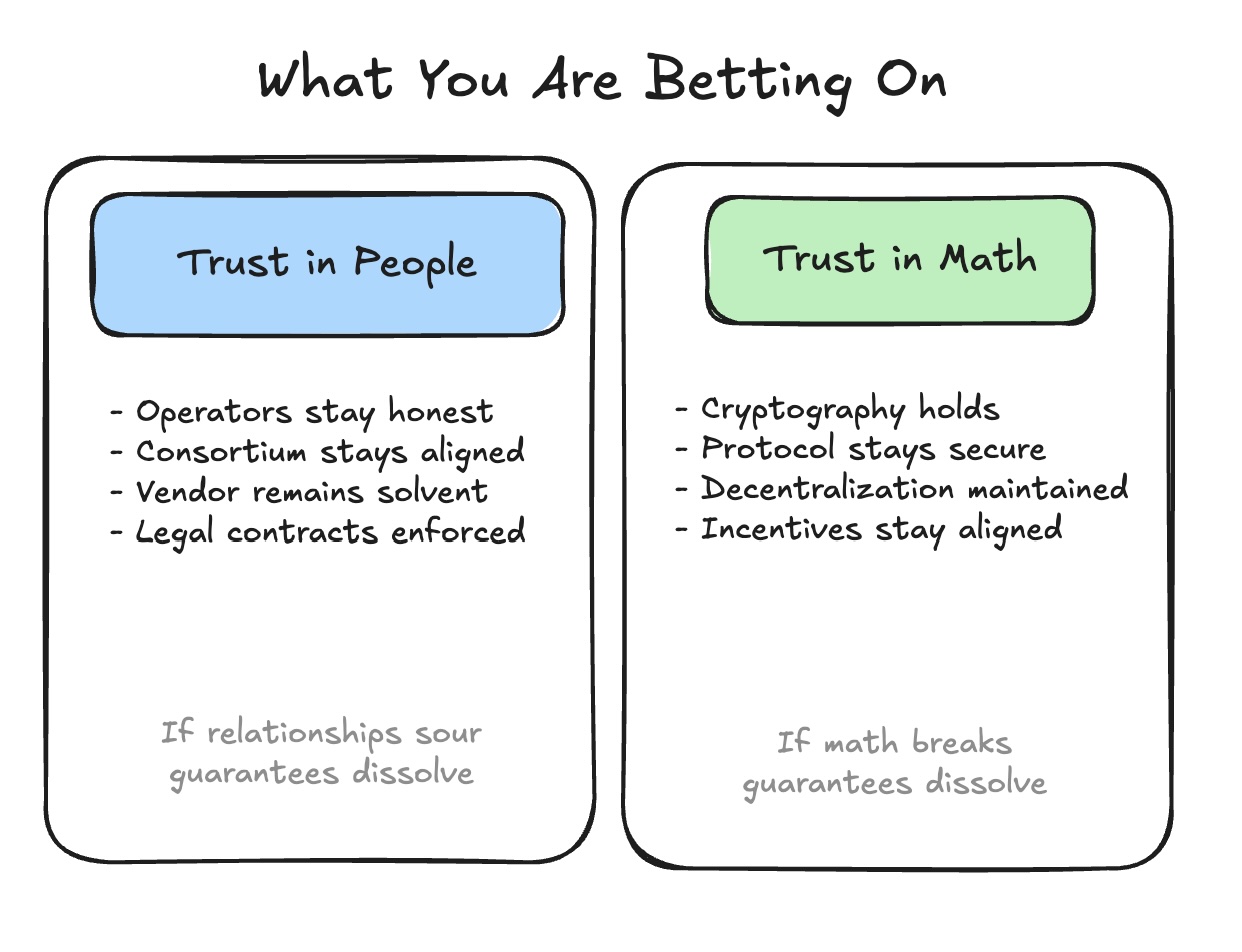

The choice comes down to privacy by policy or privacy by math.

Definitions & Scope

The terminology misleads. “Public” blockchain does not necessarily mean your data is exposed. “Private” blockchain does not mean privacy-preserving. For institutions evaluating these platforms, what matters isn’t public versus private; it’s how privacy is enforced.

Trust-based privacy (permissioned infrastructure): A known set of operators gate access. Counterparties see plaintext; non-participants are excluded by access control. Privacy depends on policy enforcement, legal agreements, and participants honoring them.

Cryptographic privacy (public infrastructure): Privacy is enforced by mathematics. Zero-knowledge proofs allow verification without disclosure. The infrastructure is public; your data is not.

This framework addresses a fundamental set of risks: a counterparty turns adversarial, a regulator demands data access years later, or an infrastructure operator gets pressured to change the rules. If you trust your consortium partners indefinitely and operate in a single jurisdiction, a standard database may suffice. Blockchains exist precisely for when trust breaks down.

1. The Permissioned Promise

For technology and risk executives at large institutions, the appeal of permissioned ledgers is obvious. They look like what you already know.

A permissioned consortium resembles traditional market infrastructure. Known parties around the table. Contractual governance. Vendor support with a runbook and a roadmap. Enterprise SLAs you can hold someone accountable to.

For a risk committee accustomed to these structures, the comfort is genuine:

- Familiar governance: You know exactly who operates the infrastructure.

- Regulatory comfort: Participants are KYC’d; access is gated; operators are regulated entities.

- No cryptographic complexity: Privacy comes from access control and contract law, not zero-knowledge proofs and novel threat models.

The promise unfolded in three waves:

- Gen 1 (Hyperledger Fabric): IBM-backed, enterprise-grade, flexible.

- Gen 2 (Corda): R3’s consortium, purpose-built for financial workflows.

- Gen 3 (Canton): DAML’s smart contract language, a Global Synchronizer for cross-domain coordination, backing from DTCC, NASDAQ, and Goldman Sachs.

These were not irrational experiments. They mapped to existing institutional mental models. The question is: what have we learned after three generations?

2. Case Study: Canton

Canton is among the most ambitious permissioned platforms in production. Understanding what it achieved, and where it hits limits, reveals whether the constraints are specific to Canton or inherent to the permissioned model.

Institutional credibility. Partnerships with NASDAQ, DTCC, Goldman Sachs, Euroclear. The headline of trillions in represented asset value1 (tokenized records of off-chain assets, not natively on-chain) represents the largest permissioned deployment to date.

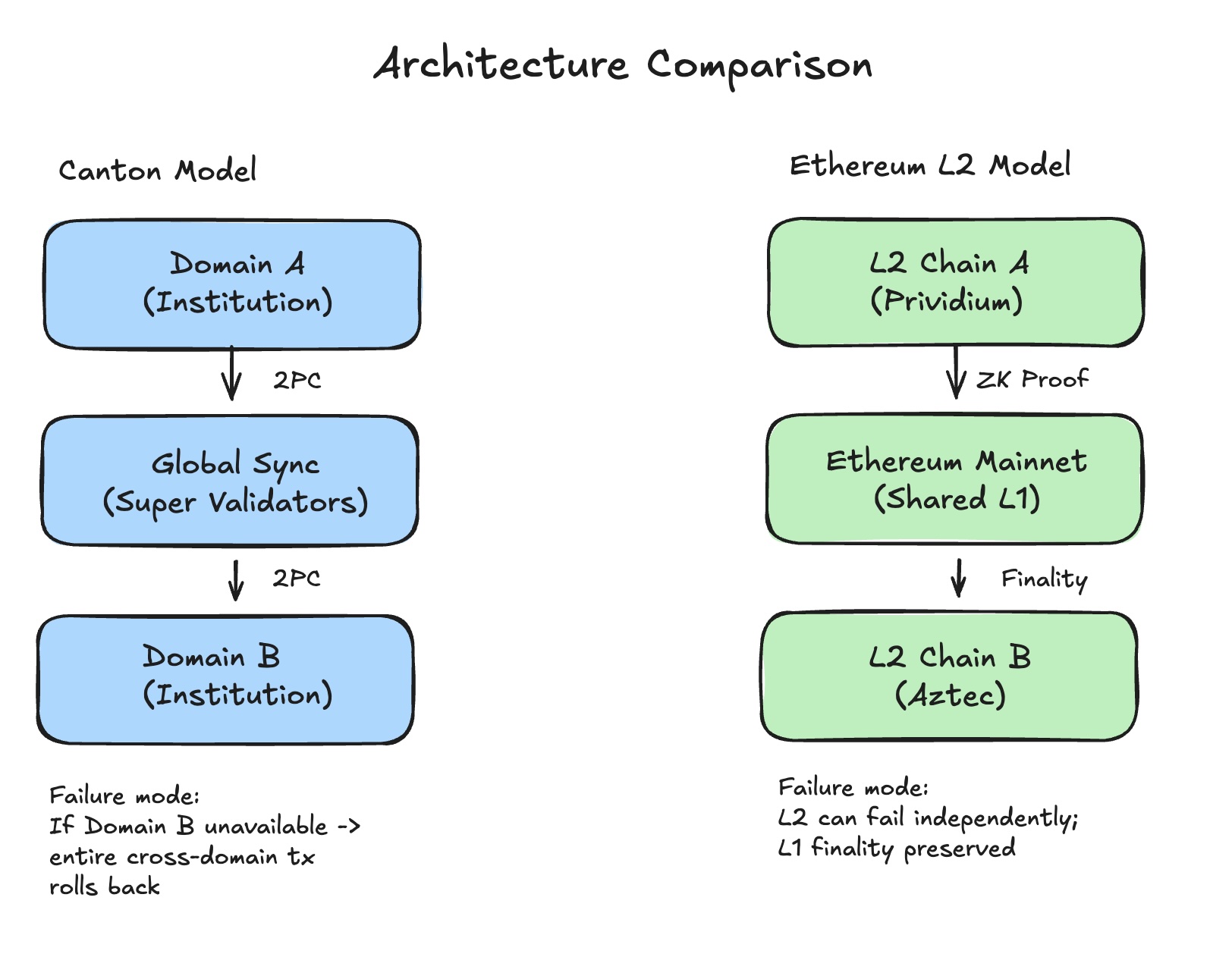

Technical sophistication. The Global Synchronizer enables cross-domain coordination. DAML’s sub-transaction privacy lets each participant see only their relevant slice. Two-phase commit (2PC) ensures multi-party transactions settle together or not at all.

Governance clarity. Super Validators (known organizations with protocol voting rights) run the network. For institutions that value knowing exactly who operates their infrastructure, this provides comfort.

Canton may be the right answer if your use case is bilateral settlement between known counterparties within a closed, legally-aligned consortium, with deterministic finality requirements and tolerance for a non-standard talent pool.

Public blockchains have their own costs: gas, coordination overhead, and MEV exposure. For pure intra-consortium workflows, Canton’s trade-offs can make sense.

But the same structural constraints we saw in Gen 1 and Gen 2 persist. Canton demonstrates that these limits are inherent to the permissioned model, not specific to any implementation.

Where Permissioned Platforms Hit Limits

Despite these achievements, Canton sits inside the same design space as Hyperledger and Corda. That space comes with constraints that matter more as the system grows.

Ecosystem isolation. Each Canton domain is a private silo. Domains cannot natively interact with Ethereum DeFi, public stablecoins, or the broader on-chain ecosystem. Any bridge requires a trusted intermediary, reintroducing the very counterparty risk that blockchains were designed to eliminate. In institutional terms, asset transferability is limited.

While the Global Synchronizer enables cross-domain transactions, liquidity tends to fragment rather than compound across separate deployments.

Vendor lock-in. DAML does not run on public EVM chains. Migration away from Canton means a full rewrite, not a port. This creates switching costs at every level: tooling, talent, and institutional knowledge.

The talent gap is real: Ethereum has thousands of monthly active developers.2 DAML has roughly 200 contributors. One precedent is COBOL in banking, still critical but increasingly difficult to staff. Hiring DAML developers at scale, over a 10-year horizon, creates key-person risk that hiring for Solidity or Rust does not.

Governance concentration. The Canton Foundation is co-chaired by DTCC and Euroclear. Protocol changes require BFT voting with a 2/3 Super Validator majority. This is consortium governance, not decentralized governance. If a regulator pressures those entities, the network’s rules change. There is no fork option.

The 2PC risk. Canton uses asynchronous two-phase commit (2PC), a coordination protocol requiring all participants to respond, to settle across domains. If any participating domain is unavailable during the commit phase, the entire transaction rolls back. As you connect more domains, failure risk correlates rather than isolates. This creates systemic operational risk: correlated failures across participants, not isolated incidents. It also creates a scalability bottleneck for global settlement, much like traditional distributed systems.

The availability math. This behavior is derived from the topology.

For any cross-domain transaction, availability is the product of participating domains. At 99% uptime each: two domains yield 98%, five domains yield 95%. The principle scales: more counterparties, lower availability. In contrast, on a public chain, if Counterparty B is offline, the L1 is still up, and Counterparty A can still post their side of the trade. Failures are isolated, not correlated.

Operational considerations. Canton’s major version migrations (2.x to 3.x) introduce breaking changes with no backwards compatibility. Budget accordingly if your production timeline spans releases.

3. Trust-Based Privacy vs Cryptographic Privacy

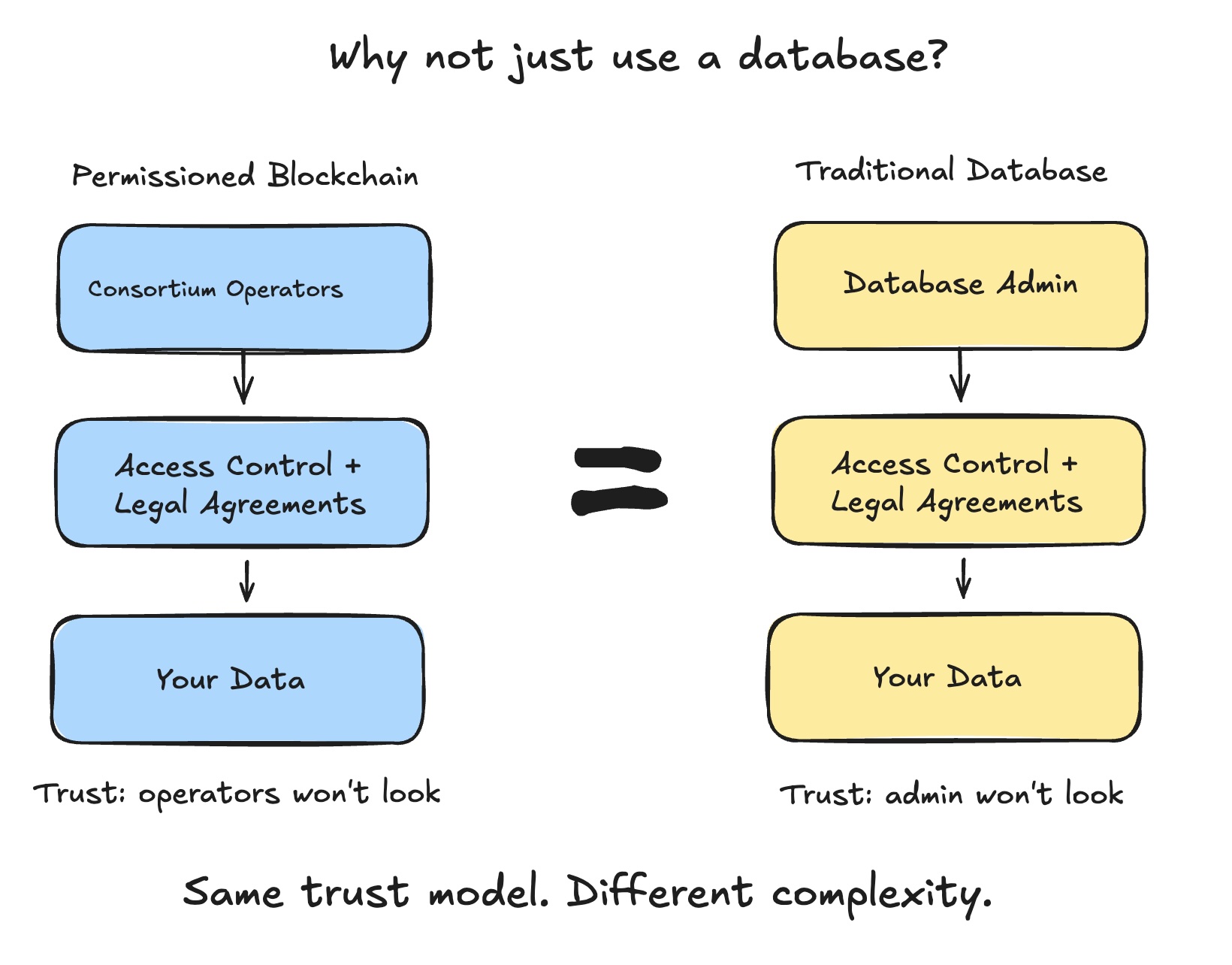

Before comparing platforms, we should ask a more basic question: why are we using blockchains at all?

Bitcoin and Ethereum answered this clearly. They demonstrated that you can have a shared ledger where no single party controls the rules, no single party can censor transactions, and no single party can rewrite history. This is what we call resilience. The value proposition is removing trust in operators and replacing it with cryptographic and economic guarantees.

Permissioned blockchains tried to capture blockchain benefits while preserving institutional control. But in doing so, they sacrificed resilience, the core value proposition. If you trust the consortium operators to run the network honestly, to respect your data boundaries, to not change the rules against your interests, you are back to trusting people. At that point, the question becomes: why not a database with legal contracts?

Trust-based privacy says: “I promise I won’t look at your data.” Operators, validators, and governance commit to respect data boundaries. If incentives shift, if regulators demand access, if governance evolves, the promise breaks.

Cryptographic privacy says: “I mathematically cannot see your data.” Zero-knowledge proofs allow verification without disclosure. The guarantee is not a policy or a contract. It is the protocol.

When trust-based privacy may suffice:

- Closed consortium, aligned incentives, single jurisdiction

- Lower-stakes, short-duration, internal workflows

When cryptographic becomes necessary:

- Adversarial or unknown counterparties

- High-stakes, long-duration commitments

- Cross-border, multi-jurisdictional exposure

Most institutional use cases, especially anything cross-border or long-duration, fall into the second category.

4. Public Blockchains

Multiple production systems now exist for cryptographic privacy on public infrastructure.

Enterprise-grade (Canton-comparable): Prividium offers ZKsync validium architecture (off-chain data, on-chain proofs) with high throughput targets3, sub-second ZK finality, KYC/SSO built in. Deutsche Bank’s Project DAMA runs here. Selective disclosure enables compliance proofs without revealing underlying data, while L1 settlement preserves composability with the broader Ethereum ecosystem. Closest analog to Canton’s feature set, with cryptographic guarantees.

Programmable privacy: Aztec provides full privacy across transactions, state, and compute. Private smart contracts in Noir. Mainnet launched late 2025; enterprise-grade throughput still maturing.

Compliance-first mechanisms: Privacy Pools (Vitalik co-authored) lets users prove funds are clean without revealing full history. Designed for the regulatory problem from day one. Live on mainnet.

Mature shielding: Railgun and similar ZK privacy pools have processed billions in shielded volume across Ethereum and L2s.

Others: Fhenix and Zama (FHE-based), Shutter Network (encrypted mempool), Renegade (dark pools), EY Nightfall and Miden (privacy rollups). For a comprehensive map of privacy solutions, see the IPTF Privacy Map.

Why this matters beyond features:

Resilience. Ethereum has operated without a complete outage since 2015, over a decade. AWS, Cloudflare, Facebook have all gone down in that period. This is the strongest argument for decentralized infrastructure.

Censorship resistance. No single entity can block transaction inclusion. For cross-border operations where jurisdictional conflicts arise, this matters.

Economics. SaaS licensing vs gas costs. Utility pricing is transparent, predictable, and has no lock-in. SaaS licensing scales with vendor leverage, not your usage. Over a decade, this compounds.

Finality. Canton’s deterministic finality4 is real. L2s are closing the gap with sub-second ZK finality. For most institutional workflows, the difference is immaterial. It matters for high-frequency trading or real-time settlement, but those are edge cases.

Regulation. Public infrastructure ≠ unregulated activity. Regulators in Singapore, EU, and elsewhere increasingly engage with public chains directly.

5. Due Diligence Checklist

Seven questions that reveal architectural constraints:

| # | Question | What It Reveals |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | The Exit Test: If the vendor disappears, does the network state survive? | Public: yes (state lives on L1). Permissioned: no. |

| 2 | Privacy Model: Is privacy enforced by policy or by mathematics? | Trust-based privacy vs cryptographic: fundamentally different risk profiles. |

| 3 | Liquidity Access: Can assets move to DeFi and stablecoins without bespoke bridges? | Ecosystem isolation vs composability. |

| 4 | Governance: Who holds the admin keys to change network rules? | Consortium voting vs protocol-level governance. |

| 5 | Talent: Is your developer pool proprietary or global? | DAML (~200 contributors) vs Solidity/Rust (thousands monthly active). |

| 6 | Portability: Can the stack move jurisdictions or platforms without a rewrite? | Vendor lock-in vs open standards and modularity. |

| 7 | Finality: Is settlement deterministic or probabilistic? | Canton advantage here. L2s closing gap. |

Comparison Matrix

How the two approaches compare across key dimensions:

| Dimension | Canton | Ethereum Privacy Stack |

|---|---|---|

| Privacy model | Trust-based privacy | Cryptographic |

| Smart contracts | DAML (non-standard stack) | Solidity/EVM (open) |

| Developer ecosystem | ~200 contributors | Thousands monthly active |

| Settlement finality | Deterministic | L1 ~12 min; L2s ~1s soft finality |

| Cross-domain atomicity | 2PC (all must respond) | Shared L1 settlement |

| Composability | Isolated domains | DeFi interoperability |

| Governance | Super Validators (consortium) | Protocol-level |

| Exit risk | Vendor-dependent | Self-sovereign |

| TCO model | SaaS | Utility |

| Track record | Canton Network: ~2 years | ~10 years, no complete outages |

Key difference: Canton failures are correlated (one domain down stops the entire cross-domain transaction). Public L2 failures are isolated (L2 down doesn’t stop the L1 or other L2s).

Closing

If you need the consortium to trust operators anyway, the blockchain adds complexity without delivering on its original promise: removing that trust requirement.

For institutions with genuine privacy requirements (adversarial counterparties, long-duration commitments, cross-border exposure, regulatory uncertainty), public blockchains with cryptographic privacy represent the architecture most aligned with what the technology was designed for.

The Ethereum privacy stack is live, battle-tested, and increasingly enterprise-ready. The seven questions above will tell you whether it fits your requirements.

For implementation patterns and institutional guidance, see the IPTF Privacy Map or contact the Institutional Privacy Task Force.

References

- Canton Technical Primer

- Global Synchronizer Docs

- DAML GitHub

- ZKsync Prividium

- Privacy Pools Paper

- Aztec Network

- Railgun

- MAS Project Guardian

- Electric Capital Developer Report

-

This figure refers to “represented” RWA (traditional assets with blockchain-based records), not “distributed” RWA where the asset itself is natively on-chain. See rwa.xyz’s framework for the distinction. ↩

-

ZKsync’s Atlas upgrade (October 2025) targets 10,000+ TPS. Actual throughput depends on transaction complexity and proving infrastructure. ↩

-

Finality refers to when a transaction is irreversibly settled. Deterministic finality means immediate and absolute. ↩