Building Private Bonds on Ethereum - Part 3

This is Part 3 of our Private Bond proof-of-concept series. In Part 1 we explored Custom UTXOs, in Part 2 we covered Privacy L2s with Aztec. Now we examine a fundamentally different approach: Fully Homomorphic Encryption.

What is Fully Homomorphic Encryption?

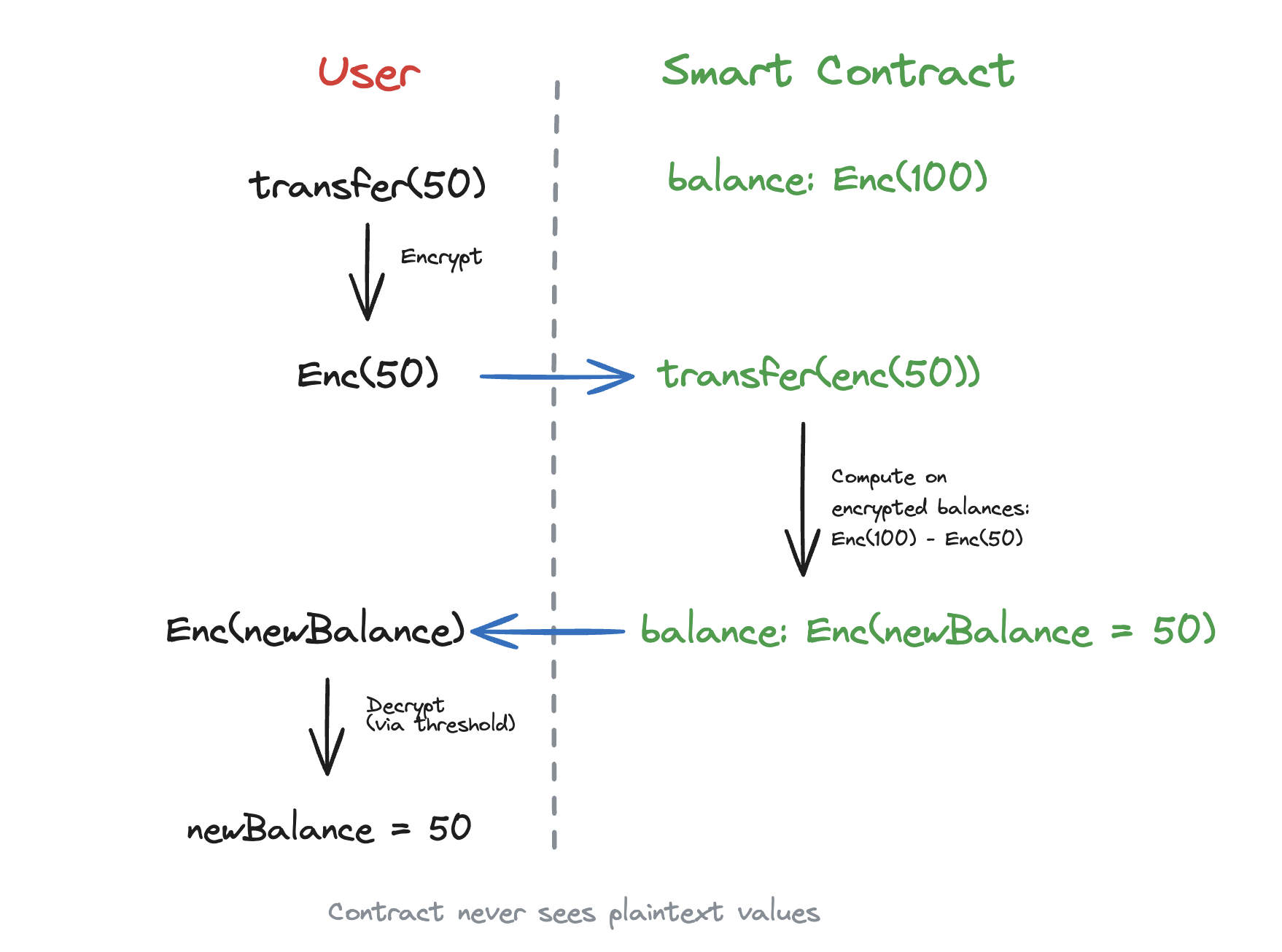

Fully Homomorphic Encryption (FHE) allows computations directly on encrypted data without ever decrypting it. The result, when decrypted, matches what you would get from computing on the plaintext.

Imagine a locked box that you can manipulate from the outside (adding, subtracting, comparing what’s inside) without ever opening it. Only the keyholder can peek inside, but anyone can perform operations.

This property makes FHE compelling for privacy-preserving finance: a smart contract can update encrypted balances, verify encrypted conditions, and transfer encrypted amounts, all while the actual values remain hidden from everyone including the blockchain observers.

Why FHE Looked Promising

Compared to ZK-based approaches, FHE offers a different paradigm with distinct trade-offs:

Direct EVM Integration. Unlike custom UTXO (which requires building notes, nullifiers, and Merkle trees from scratch) or Privacy L2s (which need their own execution environment), FHE can operate on standard Ethereum, or chains compatible with its cryptographic requirements. Identities remain standard ECDSA EOAs. You can wrap existing ERC20s directly rather than rebuilding token logic from scratch.

Familiar Programming Model. Balances remain as Solidity mappings and identities stay as standard addresses, no notes, nullifiers, or Merkle trees to manage. Your uint64 becomes an euint64, and much of the contract logic reads like a standard ERC20. But the encrypted types come with constraints: you can’t branch on encrypted values, transfers can’t revert on failure (that would leak information), and decryption requires coordinating with a threshold network. Still, for developers already comfortable with Solidity, this is a gentler starting point than writing ZK circuits in Noir or Circom.

The Encryption Model

FHE involves three key components:

Public Key: Shared network-wide. Anyone can encrypt values using this key before submitting them to the blockchain. Think of it as the lock, freely available.

Private Key: Required to decrypt ciphertexts. Here’s where things get interesting for blockchains: who holds this key?

Evaluation Key: Enables computation on ciphertexts without decrypting. This is the “magic” that lets contracts perform arithmetic on encrypted values.

The Decryption Trust Problem

In traditional encryption, you hold your own keys. But to use FHE publicly on a blockchain, we need a different model, contracts must compute on everyone’s encrypted data, and multiple parties may need decryption rights.

The solution: threshold decryption. The private key is split across multiple operators using Multi-Party Computation (MPC). To decrypt, a threshold (e.g., 9 of 13) must cooperate. No single operator can decrypt alone.

This introduces new trust assumptions:

- You trust that fewer than 1/3 of operators are malicious (colluding beyond this threshold allows key reconstruction)

- You trust the key generation ceremony was honest

- You trust the network will remain available when you need to access your funds

For institutions accustomed to custodial trust models, this may be acceptable. For those seeking self-sovereign privacy, it’s a significant trade-off versus ZK approaches where users hold their own keys.

Why Deploying FHE is Hard

The cryptography is computationally intensive. A single FHE operation can be orders of magnitude slower than a plaintext equivalent. Running this on-chain is impractical.

Operating your own decryption network requires:

- Secure key generation ceremonies

- 24/7 availability across multiple operators

- Hardware security (enclaves, HSMs)

- Coordination infrastructure

For most institutions, this operational burden exceeds the benefit. This brings us to why we chose a particular implementation path for our PoC.

The Zama Approach

We used Zama’s fhEVM for this proof of concept. A few notes on context:

The Confidential Token Standard represents broader industry work on encrypted ERC20s. Multiple teams are exploring how FHE can enable private token standards. Zama’s fhEVM is one implementation. We chose it for practical reasons: mature tooling, existing coprocessor infrastructure, and the ability to execute a PoC quickly without standing up our own threshold network.

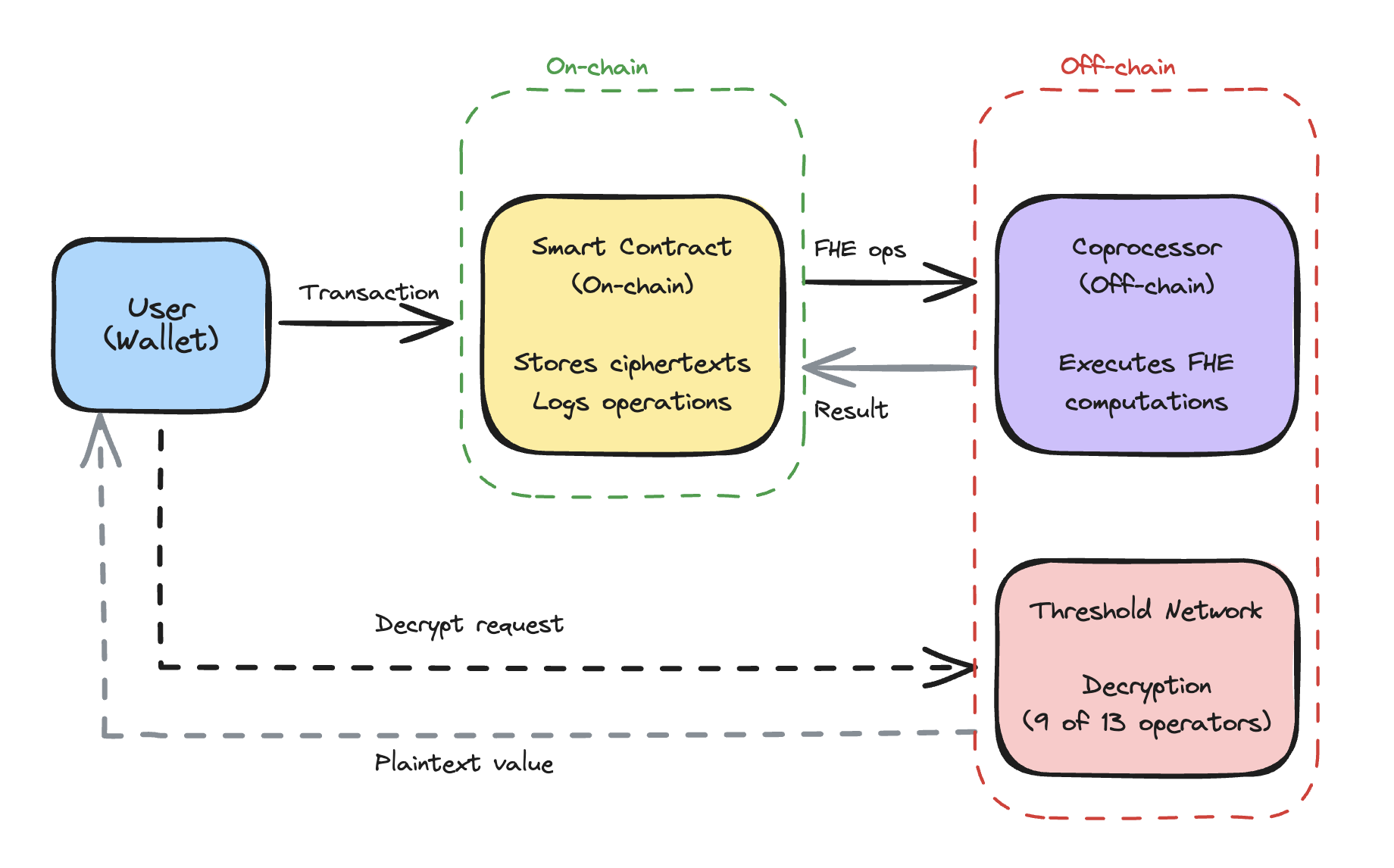

The Coprocessor Model

Zama’s architecture separates concerns:

On-chain: The smart contract stores encrypted ciphertexts and emits instructions for FHE operations. No actual FHE computation happens here; gas costs only cover ciphertext storage and operation logging.

Off-chain (Coprocessor): A network of nodes performs the actual FHE computations. When you call FHE.add(a, b), the contract records this request; coprocessors execute it and return the resulting ciphertext.

Threshold Network: When decryption is needed (e.g., user wants to see their balance), they request it through a Gateway. The threshold network coordinates: if 9 of 13 operators agree, the value is decrypted and returned.

This means:

- On-chain gas is manageable (~330K for a transfer vs. ~1M for ZK verification)

- Latency involves FHE computation (~40-80ms per operation), transfer of large ciphertexts (tens of KB each), and for decryption, threshold network coordination. End-to-end latency will be significantly higher than raw computation time

- Throughput is shared: the entire network reportedly handles 500-1000 TPS across all apps

The Smart Contract

Our ConfidentialBond.sol contract is roughly 300 lines, simpler than UTXO, comparable to Aztec. Here’s the core structure:

Public State

address public owner; // Bond issuer

bytes32 public bondId; // ISIN or identifier hash

mapping(address => bool) public whitelist; // KYC registry

uint64 public totalSupply;

uint64 public maturityDate;

Encrypted State

mapping(address => euint64) internal _balances;

mapping(address => mapping(address => euint64)) internal _allowances;

Key Functions

Whitelist Management: Standard KYC gatekeeping. Only whitelisted addresses can hold or transfer bonds.

Transfer: Similar to ERC20, but with a critical difference: it never reverts on insufficient balance. Reverts leak information. Instead, transfers silently become zero if balance is insufficient:

ebool hasEnough = FHE.le(amount, _balances[from]);

euint64 transferAmount = FHE.select(hasEnough, amount, FHE.asEuint64(0));

Users must query their balance after the transaction to confirm whether it succeeded. This uses the “User Decryption” path: the KMS nodes re-encrypt the value under the user’s public key via threshold MPC, so no individual operator sees the plaintext. However, unlike ZK approaches where balance checks are fully local, this still depends on the threshold network’s availability and honesty.

Redemption: After maturity, bondholders burn their holdings. Settlement occurs off-chain.

Audit Access: The issuer can grant regulators permission to decrypt specific balances:

function grantAuditAccess(address account, address auditor) external onlyOwner {

FHE.allow(_balances[account], auditor);

}

Access is per-ciphertext. When a balance changes (new ciphertext handle), the auditor needs fresh permission.

Comparing the Three Approaches

We’ve now built the same bond (whitelisted participants, private amounts, regulatory access) using three different privacy technologies. Here’s how they compare (see also our approach analysis and benchmarks):

| Aspect | Custom UTXO | Privacy L2 (Aztec) | FHE (Zama) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deployment | Ethereum L1 | Aztec L2 | Zama-enabled chains |

| Code Complexity | ~1000+ lines | ~200 lines | ~300 lines |

| Privacy Model | Notes + Nullifiers | Native L2 privacy | Encrypted account state |

| Who Proves? | Relayer or User | User (PXE) | Coprocessor network |

| Decryption Authority | User holds keys | User holds keys | Threshold network |

Gas & Latency

| Metric | Custom UTXO | Privacy L2 | FHE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transfer Gas | ~1.07M (Railgun ref) | Unknown | ~330K |

| Proving Latency | 2-30s | ~10s | 40-80ms (computation only, excludes ciphertext transfer) |

| Throughput | Network-bound (~15 TPS L1, ~1000+ L2) | Unknown | 500-1000 TPS shared |

What’s Hidden vs. Public

| Approach | Hidden | Public |

|---|---|---|

| Custom UTXO | Amounts, balances, tx graph | Merkle roots, nullifiers |

| Privacy L2 | Amounts, balances | Addresses (whitelist) |

| FHE | Amounts, balances | Addresses, tx existence |

Trade-offs

Custom UTXO offers the strongest privacy guarantees: even addresses are obscured via nullifiers, and users control their own keys. Railgun and similar systems prove the model works in production. But implementation complexity is significant. Our PoC required building notes, Merkle trees, and nullifier management from scratch. Nullifiers also accumulate forever, creating storage concerns at scale (mitigations like epoch-based pruning are being researched but not yet deployed).

Privacy L2s like Aztec handle the hard parts for you: notes, proofs, encryption. Our contract was just 200 lines. Private composability is native, meaning your bonds could interact with private lending or swaps on the same L2. The catch: neither Aztec nor Miden are live yet (both scheduled for launch later in 2026), so we can’t measure real costs. And the learning curve exists: Noir is not Solidity.

FHE is the gentlest onramp. If you know Solidity, you can write confidential contracts quickly. Standard wallets work. But you trade self-custody for threshold trust: your funds depend on the network’s availability, and if a quorum of KMS operators collude, they could reconstruct the decryption key. In normal operation, no individual operator sees plaintext (user decryptions are re-encrypted under the user’s key via MPC). For institutions already comfortable with custodial relationships, this may be acceptable. For those seeking self-sovereign privacy, it’s a meaningful concession.

It’s worth noting that the coprocessor model isn’t exclusive to FHE. TACEO’s Merces (built from their private_deposit codebase) demonstrates a similar architecture using MPC instead: a three-party network maintains secret-shared balances and generates collaborative SNARKs (Groth16 proofs) to verify state transitions on-chain. This is an application of the co-SNARK pattern, where multiple parties jointly produce a ZK proof without revealing their individual inputs. The trust assumption is the same, you rely on an honest majority of operators rather than holding your own keys, but the MPC path avoids FHE’s computational overhead and adds native verifiability through the co-SNARK proofs. We could have built our bond PoC on this stack as well.

Conclusion

Three paths to the same destination: private institutional bonds on Ethereum. Each works. Each makes different trade-offs on privacy, complexity, and trust. The choice depends on what your institution prioritizes.

The code for all three approaches is available in the IPTF PoC repository, with detailed specs and benchmarks. For a broader view of privacy patterns and vendor landscape, see the IPTF Knowledge Map. We welcome feedback and contributions.

Next up: Private Stablecoins, exploring shielded pools and on-chain KYC registries for compliant private payments.