Building Private Bonds on Ethereum - Part 2

In Part 1, we built private zero-coupon bonds from scratch on Ethereum. The result worked, but required three distinct components: a Noir circuit for ZK proofs, a Solidity contract for on-chain state, and a Rust wallet for key management and proof generation. We also needed a trusted relayer (the issuer) to coordinate transactions and prevent frontrunning.

That architecture raised an obvious question: what if the network itself handled all this complexity?

This is precisely what privacy-focused L2s offer. Instead of bolting privacy onto a transparent ledger, you start with a network where notes, nullifiers, and encrypted execution are first-class primitives. The same protocol we built manually becomes a straightforward smart contract.

We chose Aztec for this prototype because it has a running testnet and mature tooling, making it fast to iterate. Other projects pursue similar goals with different tradeoffs: Miden takes a different approach to client-side proving, and Aleo builds on a separate L1. The concepts in this post apply broadly to any system that enshrines UTXO-style privacy at the protocol level.

What Aztec Gives You For Free

When we built the custom UTXO system, we had to implement every privacy primitive ourselves. Aztec provides these as protocol infrastructure.

Notes and nullifiers are native to the execution model. When you transfer private tokens, the network handles note creation, commitment insertion into the Merkle tree, and nullifier tracking. No custom circuit logic required.

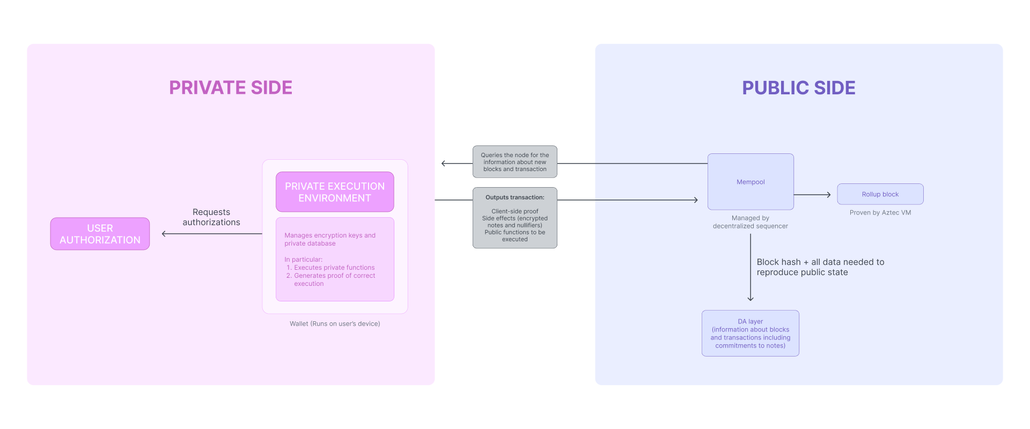

ZK proof generation happens in the Private Execution Environment (PXE), a client-side component that runs on the user’s machine. The user’s secrets never leave their device. The PXE generates proofs locally, then submits them to the network for verification.

Encrypted mempool solves frontrunning without a trusted relayer. In our custom implementation, the issuer had to batch transactions to prevent competitors from seeing pending trades. On Aztec, transactions are encrypted before entering the mempool. Sequencers process them without knowing the contents until execution.

Source: Aztec Documentation

Source: Aztec Documentation

Decentralized sequencing removes the single point of trust. Our custom system required the issuer to relay all transactions. On Aztec, a decentralized sequencer network orders and executes transactions. The issuer remains important for business logic (whitelist management, distribution), but loses their privileged position in transaction ordering.

The practical impact: we went from coordinating three codebases to writing one contract.

The Contract: 200 Lines of Noir

Aztec contracts are written in Noir, a Rust-like language designed for ZK circuits. If you have written Rust or Solidity, the syntax will feel familiar.

The key difference from Solidity is that a single contract can hold both public and private state, with functions that operate on either (or both). Public state works like traditional blockchain storage: visible to everyone, updated through public functions. Private state lives in encrypted notes that only the owner can decrypt.

Here is the core storage structure:

#[storage]

struct Storage<Context> {

// Public: visible to everyone

owner: PublicMutable<AztecAddress, Context>,

whitelist: Map<AztecAddress, PublicMutable<bool, Context>, Context>,

total_supply: PublicMutable<u64, Context>,

maturity_date: PublicMutable<u64, Context>,

// Private: encrypted notes per user

private_balances: Owned<BalanceSet<Context>, Context>,

}

The BalanceSet is Aztec’s built-in primitive for private token balances. It handles note management, nullifier generation, and balance proofs internally. What took us hundreds of lines of circuit code in Part 1 becomes a single type annotation.

What we kept from the custom implementation:

- Whitelist enforcement (KYC/AML compliance)

- Issuer role for distribution and administration

- Maturity date checking for redemption

What disappeared:

| Component | Custom UTXO | Aztec L2 |

|---|---|---|

| ZK circuit | 200+ lines of Noir | Built into BalanceSet |

| Proof verifier | Generated Solidity contract | Protocol-native |

| Merkle tree logic | Contract + off-chain sync | Protocol-native |

| Memo encryption | ECDH + ChaCha20-Poly1305 | Protocol-native |

| Nullifier tracking | Custom mapping + logic | Protocol-native |

The bond contract itself is around 200 lines. The entire codebase (contract + test script) fits in a single directory.

A private transfer looks like this:

#[external("private")]

fn transfer_private(to: AztecAddress, amount: u64) {

let sender = self.msg_sender().unwrap();

// Check whitelist (reads public state from private context)

self.enqueue_self._assert_is_whitelisted(sender);

self.enqueue_self._assert_is_whitelisted(to);

// Transfer notes (all ZK magic happens inside BalanceSet)

self.storage.private_balances.at(sender).sub(amount as u128);

self.storage.private_balances.at(to).add(amount as u128);

}

Notice the enqueue_self pattern. Private functions cannot directly read public state (that would leak information about which public data the private transaction accessed). Instead, they enqueue public function calls that execute after the private portion completes. The whitelist check happens publicly, but by then the private transfer details are already committed.

A note on address visibility: The enqueued whitelist checks reveal the sender and recipient addresses publicly, even though the transfer amount remains private. This was a deliberate design choice: our requirements stated that participant identities can be visible (institutions typically need to know their counterparties for compliance). For use cases requiring participant anonymity, a Merkle-ized whitelist would allow users to prove membership without revealing their specific address. We discuss this approach in the “Privacy Model Differences” section below.

This public/private dance is the core programming model difference from Solidity. You think in two phases: what happens privately (with user secrets), then what happens publicly (visible state updates).

Authwit: The Missing Primitive

In Part 1, atomic swaps required careful coordination. Both parties had to submit proofs to the relayer, who batched them into a single transaction. If either proof was missing or invalid, the whole swap failed. More fundamentally, the issuer-as-relayer was a single point of failure: if the relayer went offline, no trades could settle.

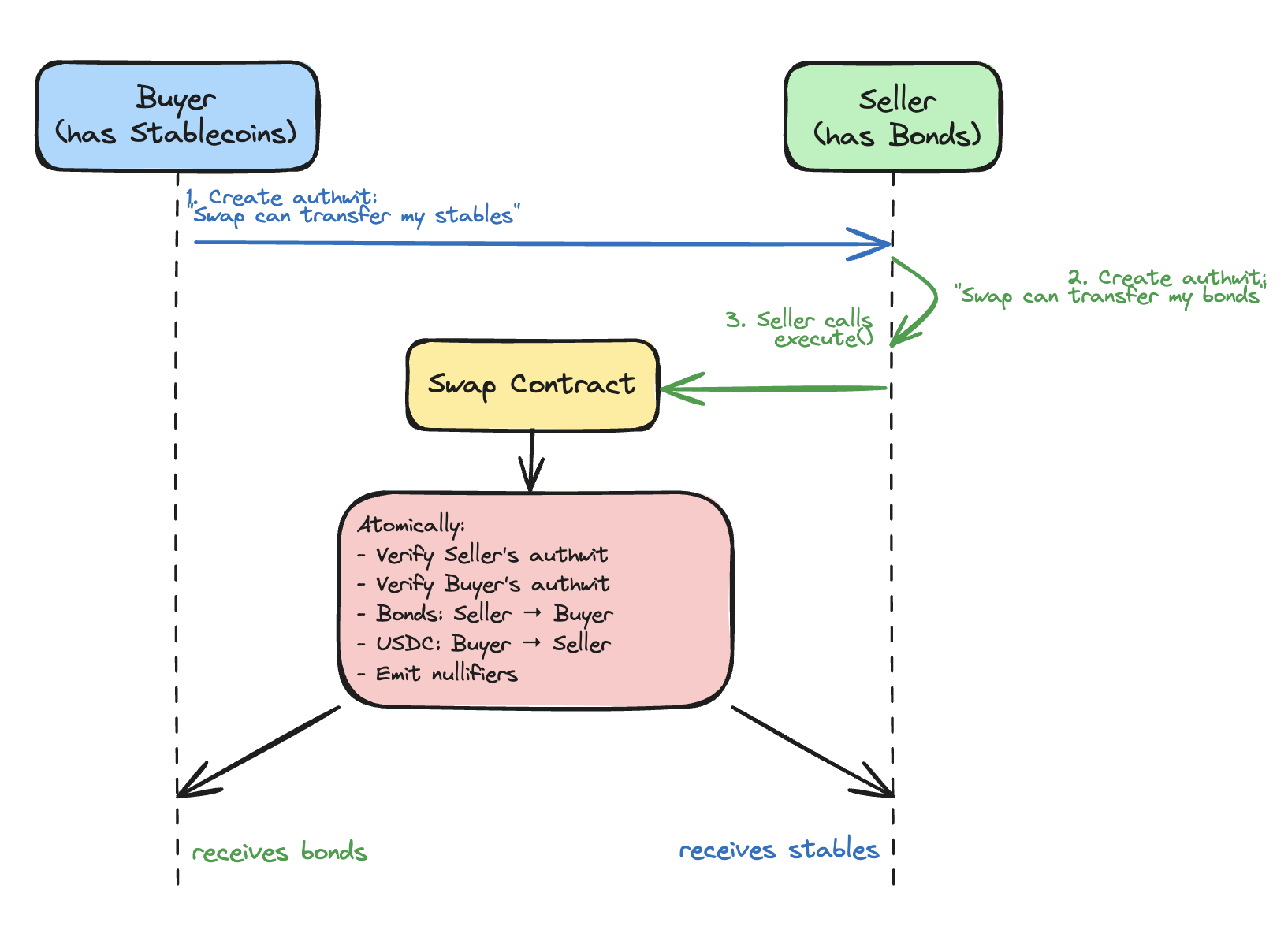

Aztec introduces a cleaner pattern called Authentication Witness (authwit). Think of it as a cryptographic IOU: “I authorize contract X to do action Y with my assets, under conditions Z.”

Why not just use ERC-20’s approve pattern? It does not work with private state. When Alice approves Bob to spend her tokens on Ethereum, that approval is public and persistent. Anyone can see it, and Bob can use it repeatedly until Alice revokes it.

With private notes, there is no public balance to approve against. Alice’s notes are encrypted. Only she knows their contents. Even if she wanted to grant a blanket approval, the spender would need her secrets to construct a valid proof.

Authwit solves this differently:

| Aspect | ERC-20 Approve | Authwit |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | Blanket allowance up to limit | Exact action with exact parameters |

| Visibility | Public on-chain | Private until execution |

| Reuse | Persists until revoked | Single-use (nullified after) |

| Revocation | Requires on-chain transaction | Emit nullifier directly |

For atomic DvP (Delivery-vs-Payment), the flow becomes:

- Buyer creates authwit: “Swap contract can transfer my stablecoins”

- Seller creates authwit: “Swap contract can transfer my bonds”

- Seller calls

execute()on the Swap contract - Contract verifies both authwits, atomically swaps assets

- Both authwits are nullified (cannot be replayed)

The key property: both parties commit to exact terms before execution. The seller cannot receive less than expected. The buyer cannot pay more. If either authwit is missing or mismatched, the transaction fails atomically.

Why this is secure: Authwits grant permission to the contract, not to the counterparty. The Buyer cannot directly use the Seller’s authwit. Only the DvP contract can act on it, and the contract is programmed to execute both transfers atomically or neither.

Our bond contract includes a transfer_from function that leverages this pattern:

#[authorize_once("from", "nonce")]

#[external("private")]

fn transfer_from(from: AztecAddress, to: AztecAddress, amount: u64, nonce: Field) {

// Authwit verification happens automatically via the macro

self.enqueue_self._assert_is_whitelisted(from);

self.enqueue_self._assert_is_whitelisted(to);

self.storage.private_balances.at(from).sub(amount as u128);

self.storage.private_balances.at(to).add(amount as u128);

}

The #[authorize_once] macro handles authwit verification and nullifier emission. A DvP contract would call this function, and the call only succeeds if the from address previously created a matching authwit.

Privacy Model Differences

The custom UTXO system and Aztec solve the same problem with different trust assumptions and composability characteristics.

Custom UTXO on EVM:

The issuer sees all transaction details in plaintext and can provide this data to regulators on demand. Participants trust the issuer not to abuse this access (acceptable when the issuer is a regulated institution).

This model matches how institutional bond markets already work. The issuer is the central party. They know all participants, manage the whitelist, and coordinate settlement. The privacy is asymmetric: hidden from competitors and the public, fully visible to the issuer and regulators.

Aztec L2:

Users control their own keys. Aztec accounts have separate key pairs for nullifiers (spending), viewing (decrypting notes), and signing (transaction authorization). The key architecture is designed for selective disclosure: viewing keys can be shared without compromising spending ability.

Notably, nullifier keys are app-siloed (preventing cross-application spending correlation), but viewing keys are account-wide. For per-contract disclosure, applications would need to implement custom encryption at the note level.

This model enables an auditing trail: the issuer shares their own viewing key with regulators to prove all issuances and distributions, while each regulated investor independently shares their viewing key to demonstrate their holdings. No centralized key collection required. The tradeoff is that viewing keys expose all activity across all Aztec applications, not just the bond contract.

Composability:

The Aztec model enables something the custom approach cannot: direct interoperability with other private contracts. A bond contract can call a private stablecoin contract for atomic settlement without either party revealing amounts to the network. The same authwit pattern works across any Aztec contract.

In the custom UTXO approach, each private system is an island. Atomic swaps between different private assets would require a shared relayer or cross-system coordination protocol. On Aztec, it is just two contract calls in the same transaction.

This shared infrastructure also means a larger anonymity set. On Aztec, all private applications contribute to the same global note tree and nullifier set. Your bond transaction hides among all network activity. With a custom UTXO contract on EVM, your anonymity set is limited to other users of that specific contract.

Throughput considerations:

The custom UTXO model allowed the issuer to batch transactions aggressively. As the sole relayer, they could accumulate proofs and submit them in optimized batches, achieving high throughput limited only by Ethereum’s block space and the relayer’s infrastructure.

On Aztec, throughput is bound by the sequencer network and the L1 commitment cadence. Each transaction requires sequencer ordering, execution, and eventual settlement to Ethereum for hard finality. The decentralization that removes the trusted relayer also distributes (and potentially limits) throughput.

For high-frequency trading desks processing thousands of transactions per second, this matters. For typical institutional bond markets (where trades happen over minutes or hours, not milliseconds), current throughput could fit requirements.

A quick win: private whitelists.

Our implementation uses a public whitelist (Map<AztecAddress, bool>) because the requirements explicitly stated that participant identities can be visible. But Aztec makes it straightforward to go further.

A private whitelist would store only a Merkle root on-chain. The issuer maintains the full list off-chain and provides membership proofs to whitelisted participants. When transferring bonds, users prove they belong to the whitelist without revealing which specific address they are.

This adds some centralization (the issuer controls the off-chain list), but that is already the case for KYC compliance. The cryptographic overhead is minimal in Noir. For institutions that want participant privacy beyond what was originally required, it is a few lines of code away.

Conclusion

We rebuilt the same private bond protocol on a privacy L2 and ended up with significantly less code. The complexity did not disappear; it moved into protocol infrastructure where it benefits from shared primitives, audited implementations, and ongoing maintenance by the network developers.

The key improvements over our custom UTXO approach apply to any network that enshrines privacy at the protocol level:

- No custom cryptographic plumbing. Note management, nullifier tracking, and proof generation are handled by the network. Your contract focuses on business logic.

- Atomic operations without a trusted relayer. Patterns like authwits (or equivalent primitives on other networks) enable DvP where either party can trigger execution once both have committed.

- Larger anonymity set. All applications on the network share the same note tree. Your bond transactions hide among all network activity, while whitelisting ensures you still control who trades your assets.

The tradeoffs are also structural to this approach:

- You inherit the network’s constraints. Key architecture, throughput limits, and fee models are set by the protocol, not your team.

- Maturity varies. Aztec’s execution layer isn’t live yet; Miden is earlier in development;

- Vendor coupling. Building on a specific L2 means adopting its programming model, tooling, and roadmap.

For teams that want to ship a prototype without building cryptographic infrastructure from scratch, privacy L2s offer a faster starting point. For teams that need precise control over every layer, the custom UTXO approach from Part 1 remains viable.

The full implementation (on Aztec) is open source, with a detailed specification covering the protocol design.

In Part 3, we will explore a third approach: fully homomorphic encryption (FHE). Where UTXO models hide data by never putting it on-chain, FHE allows computation on encrypted data directly. Different cryptography, different tradeoffs, same institutional requirements.