Building Private Transfers on Ethereum with Shielded Pools

Every stablecoin transfer on Ethereum is public. When an institution moves USDC to a supplier, that payment is visible to every competitor, analyst, and observer on the network. Treasury positions, supplier relationships, settlement timing and payment frequency are visible to anyone with a block explorer.

Traditional banking solved this decades ago. Payment details are visible only to the counterparties and their banks. On public blockchains, institutions don’t have that option, unless we build it.

In a previous post, we built private zero-coupon bonds using a UTXO model and ZK proofs. That PoC demonstrated the cryptographic primitives: commitments, nullifiers, Merkle trees, encrypted memos. This one tackles a different problem: stablecoin payments where compliance gating, not just privacy, is the primary design constraint.

This post walks through a proof-of-concept that brings banking-grade payment privacy to stablecoin transfers on Ethereum L1. The design prioritizes compliance-first privacy: only KYC-verified participants can enter the system, and viewing keys enable selective disclosure for regulators. The full implementation is open source, with a detailed specification.

The Gated Shielded Pool

The protocol implements four mechanisms working together.

Attestation-gated entry. Before a participant can deposit tokens, a compliance authority must issue a KYC attestation. This attestation is stored as a leaf in an on-chain Merkle tree (the attestation tree). When depositing, the user proves with a zero knowledge proof, that their public key appears in the attestation tree. No identity information is revealed on-chain; the proof confirms only that “this depositor has been verified.”

UTXO model. The commitment/nullifier model below builds on the previous post, skip to Three Operations if you’re already familiar. Funds inside the pool exist as encrypted notes. Each note contains a token address, an amount, the owner’s public key, and a random salt:

Note {

token: address // ERC-20 contract (e.g., USDC)

amount: u256 // Token amount in raw units

owner_pubkey: Field // poseidon(spending_key)

salt: Field // Random blinding factor

}

The note’s commitment: poseidon(token, amount, owner_pubkey, salt) is stored on-chain. Poseidon is a hash function designed to be efficient inside ZK circuits, which makes it the natural choice for commitment schemes where the hash must be proven correct in zero knowledge. Nothing about the note’s contents is visible from the commitment alone.

To spend a note, the owner produces a nullifier: poseidon(commitment, spending_key). The contract records the nullifier to prevent double-spending but cannot link it back to the original commitment without the spending key. This is the same commitment/nullifier pattern used by Zcash and Railgun, adapted here with compliance gating at the entry point.

Dual-key architecture. Each participant holds two keys: a spending key (authorizes transfers) and a viewing key (decrypts transaction history). The spending public key is derived as poseidon(spending_key), keeping it ZK-friendly for use inside circuits. The viewing public key is derived on the secp256k1 curve (k256), which enables standard ECDH key agreement for encrypting notes to recipients. This separation matters for institutions. A compliance officer or regulator can hold a viewing key to audit all transactions for a given participant without being able to move funds. The spending key never leaves the participant’s control.

Relayer abstraction. Third-party relayers submit transactions on behalf of users, paying gas and preventing timing correlation between a user’s identity and their on-chain activity. Relayers cannot steal funds, nor can they ever see spending keys, and users can switch relayers or submit directly to the L1 if needed.

Three Operations

The shielded pool supports three operations: deposit (shielding), transfer, and withdraw (unshielding).

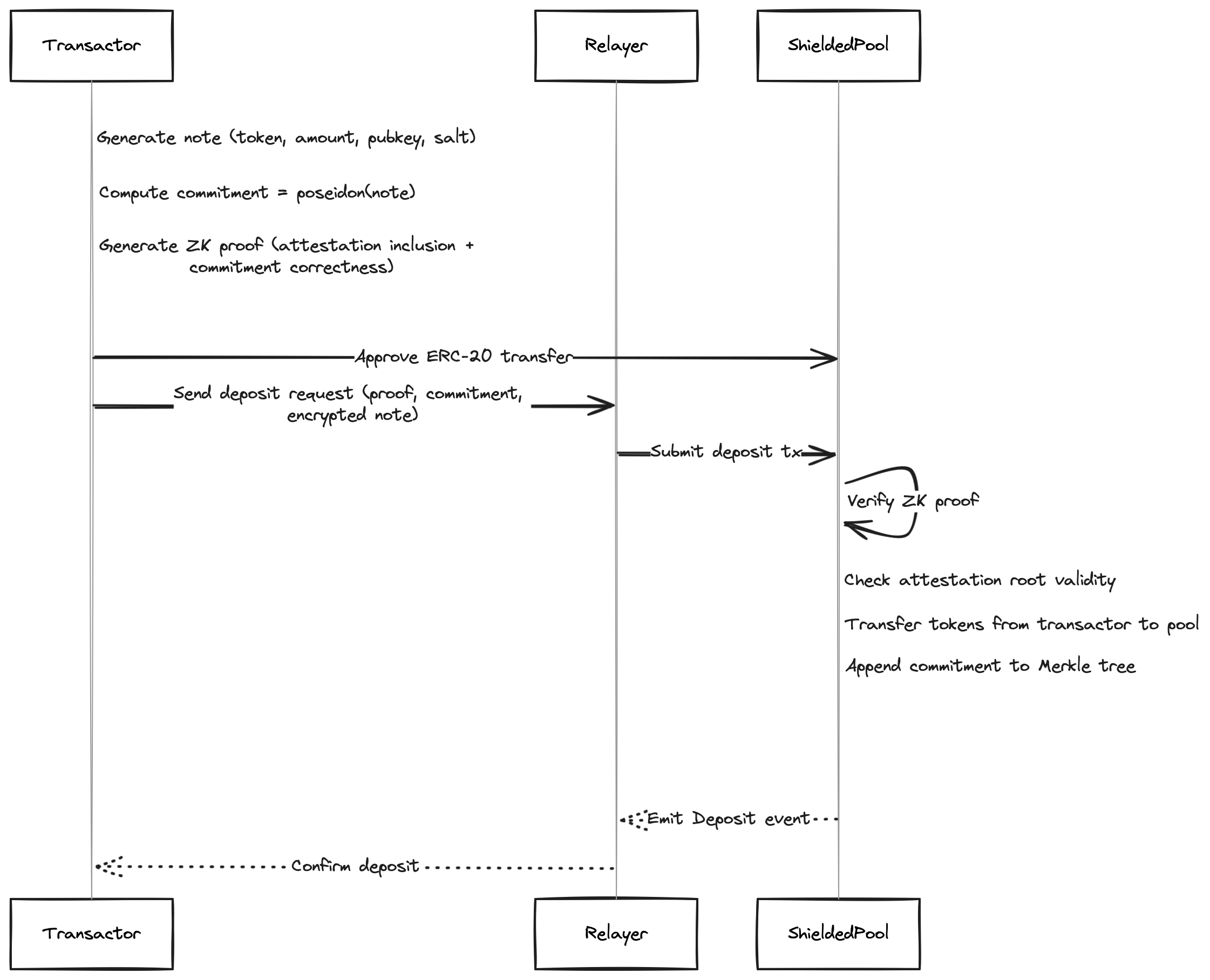

Deposit

A user converts public ERC-20 tokens into a private note. The deposit circuit enforces two facts: that the note commitment is correctly formed, and that the depositor has a valid KYC attestation (Merkle inclusion proof against the attestation tree root). The contract then performs the following actions:

- Verifies the ZK proof

- Uses

transferFromto pull approved tokens into the pool contract, where they are held in aggregate under the contract’s withdrawal logic and subject to its governance and upgrade controls. - Appends the new commitment to the commitment Merkle tree.

The deposit proof’s public inputs are the commitment, token address, amount, and the current attestation tree root. Everything else stays private: the depositor’s public key, the salt, the attester’s identity, and the attestation details (when it was issued, when it expires). An observer sees that someone deposited a known amount of a known token, but cannot determine who deposited it or which compliance authority verified them.

One caveat: deposit and withdrawal amounts are public, so matching amounts can reveal a link, especially in small pools. Transfers hide amounts, but shielding and unshielding do not. Split notes via transfers before withdrawing to reduce correlation.

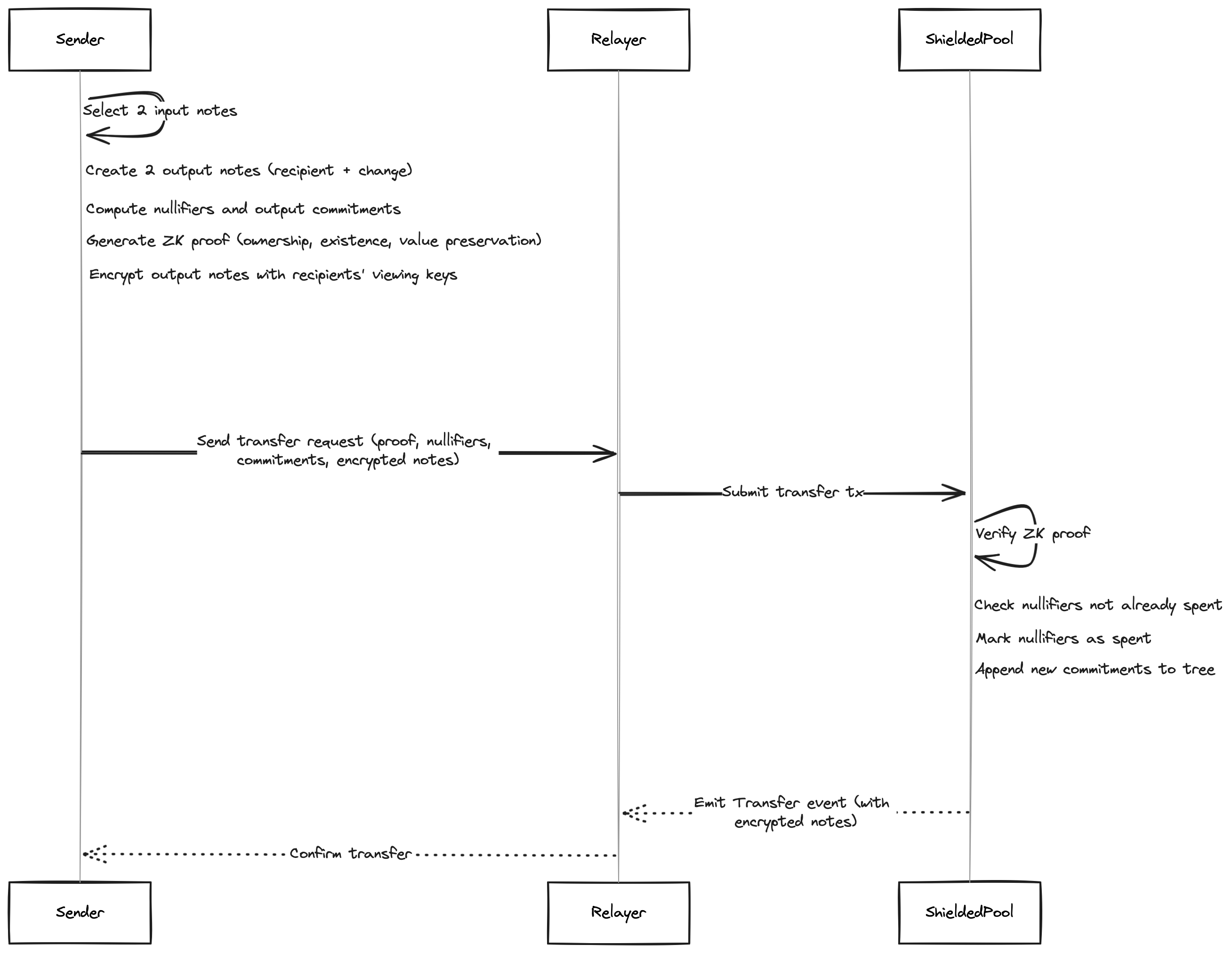

Transfer

This is the core operation. A sender spends two input notes and creates two output notes: one for the recipient, one for change. This is the 2-in-2-out pattern. If only one input is needed, the second is padded with a zero-value note.

The transfer circuit enforces six constraints:

- Ownership: the sender knows the spending key for both input notes

- Existence: both input commitments are in the commitment tree (Merkle inclusion proof)

- Nullifier correctness: nullifiers are correctly derived from the commitments and spending key

- Output formation: output commitments are well-formed

- Value preservation:

amount_in_0 + amount_in_1 == amount_out_0 + amount_out_1 - Token consistency: all four notes use the same token address

After verification, the contract marks both input nullifiers as spent and appends the two new commitments to the tree.

The sender encrypts each output note for its recipient using ECDH: the sender generates an ephemeral key pair, computes a shared secret with the recipient’s viewing public key, derives an encryption key via HKDF, and encrypts the note contents with ChaCha20-Poly1305. The ciphertext is included in the transaction’s Transfer event. Recipients scan these events, attempt decryption with their viewing key, and discover notes addressed to them.

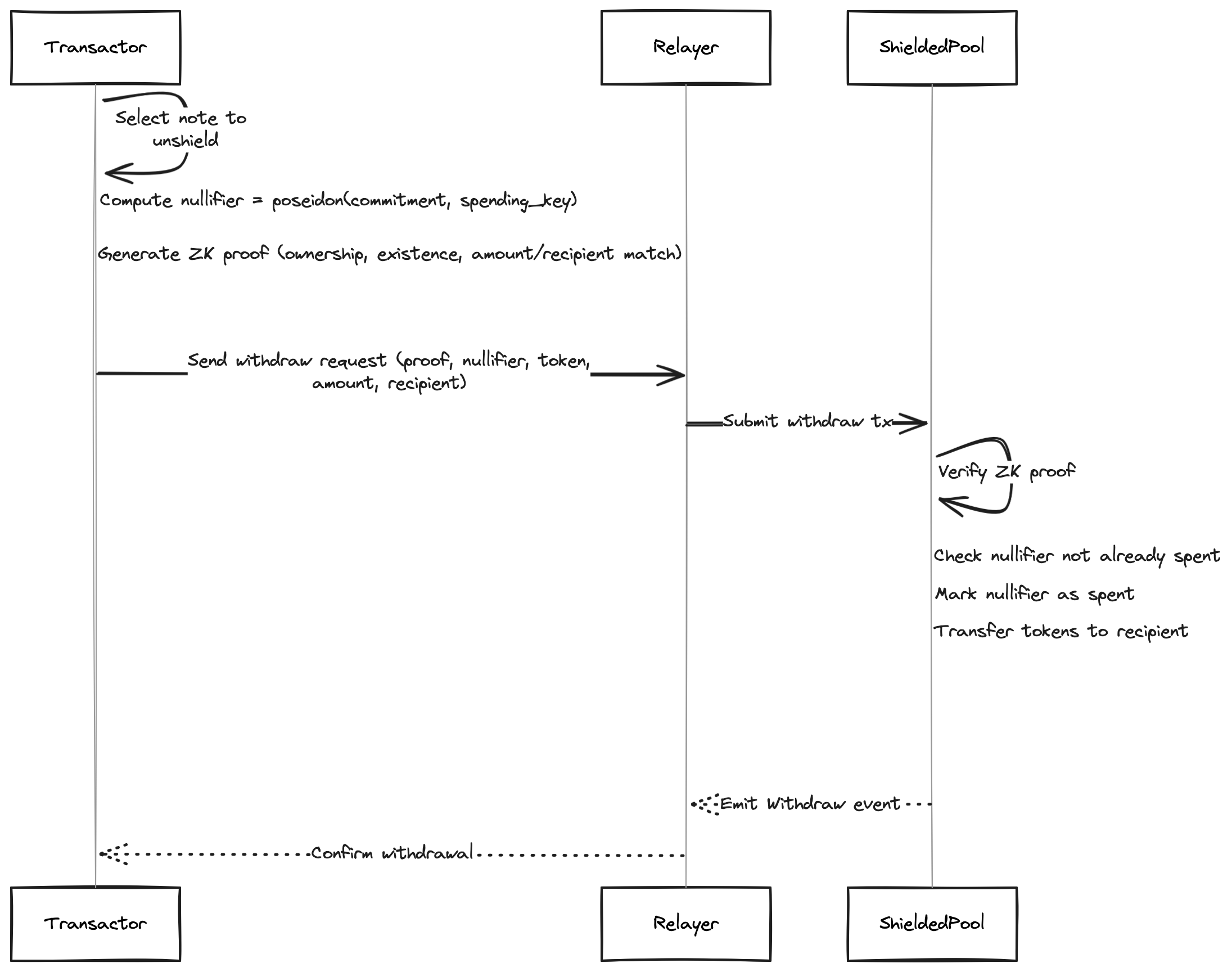

Withdraw

Converts a private note back to public tokens. The user proves they own a note in the commitment tree and that the claimed amount and recipient match. The contract verifies the proof, marks the nullifier as spent, and transfers tokens to the specified address.

Architecture

The implementation spans three layers.

Noir circuits. Three circuits: deposit, transfer, and withdraw encode the cryptographic constraints described above. Proofs are generated using UltraHonk via Barretenberg.

Solidity contracts. The ShieldedPool contract manages commitments, nullifiers, and token custody. The AttestationRegistry manages the KYC attestation tree with support for adding and revoking attestations. A CompositeVerifier delegates proof verification to circuit-specific verifier contracts auto-generated from Noir. Both Merkle trees use LeanIMT, an incremental Merkle tree implementation from PSE’s zk-kit.

Rust client. The off-chain client handles key derivation, note management, proof generation, and contract interaction. It uses Alloy for Ethereum RPC and follows a ports-and-adapters pattern with two core traits: Prover (generates proofs) and OnChain (abstracts all contract reads and writes). This makes the client testable at every layer: mock implementations for unit tests, local Anvil node for integration tests, with a path to testnet deployment using the same interfaces.

| Layer | Tools |

|---|---|

| Circuits | Noir, UltraHonk (Barretenberg) |

| Contracts | Solidity, Foundry, LeanIMT |

| Client | Rust, Alloy, light-poseidon, k256 |

| Encryption | ECDH + HKDF + ChaCha20-Poly1305 |

| Hashing | Poseidon (BN254) |

Compliance Without Compromise

Consumer privacy protocols like Tornado Cash maximize anonymity at the expense of compliance. This design takes the opposite approach: privacy is a feature of the compliance architecture, not a workaround for it.

Gated entry, not gated exit. Only KYC-verified participants can deposit. But once funds are in the pool, transfers between verified participants are private. This mirrors how traditional banking works: you verify identity at account opening, not at every payment.

Revocable attestations. If a participant becomes sanctioned or their KYC expires, the compliance authority revokes their attestation by removing the leaf from the attestation tree. This prevents new deposits. Critically, it does not freeze funds already in the pool, and the participant can still withdraw. This avoids the legal and operational complexity of asset freezing while cutting off future access.

Selective disclosure. Viewing keys grant read-only access to a participant’s full transaction history. An institution can share viewing keys with auditors or regulators without exposing other participants’ data and without granting spending authority. This supports AML/CFT monitoring obligations without centralizing surveillance.

No issuer modifications. The protocol works with existing ERC-20 stablecoins (USDC, EURC) without changes to token contracts, special hooks, or issuer cooperation. Tokens are locked in the shielded pool contract on deposit and released on withdrawal.

Threat model. The security properties depend on who the adversary is. A public observer sees commitments and nullifiers but cannot link them or extract note contents without a spending or viewing key. In the target architecture, a malicious relayer can delay or refuse to submit transactions, but cannot steal funds or link transactions. The user can always bypass the relayer and submit directly (see Limitations for the current PoC state). A compromised viewing key leaks read access to one participant’s history, but cannot be used to spend funds or decrypt other participants’ notes. A malicious compliance authority could issue attestations to unauthorized parties, which is why production deployments should require multi-sig or DAO governance for attester authorization.

The Anonymity Set Tradeoff

Privacy in a shielded pool is only as strong as the number of indistinguishable participants. The more users holding notes in the pool, the harder it is for an observer to link a nullifier to a specific commitment. This creates a fundamental tension in the gated design.

Permissionless protocols like Railgun take one side of this tradeoff: allow anyone to deposit, maximizing the anonymity set, and use Private Proofs of Innocence to let users prove their funds are not linked to known malicious sources. The pool is large, but it contains unknown participants. A gated pool like this PoC takes the other side: restrict entry to KYC-verified parties, giving compliance certainty at the cost of a smaller anonymity set.

In the early stages of deployment, this tradeoff is real. A pool with ten participants offers weak unlinkability regardless of the cryptography. However, the anonymity set is not permanently small, it scales with adoption.

Consider a bank issuing a stablecoin or tokenized deposit and running a shielded pool for its customers. Every customer who deposits into the pool becomes part of the anonymity set. The bank’s own treasury operations, including payroll, vendor payments and interbank settlements add further cover traffic. As the customer base grows, so does privacy. Both the bank and its customers accumulate anonymity through normal usage, not through any special action.

Institutions prefer verifiable cleanliness over unknown provenance.

Limitations

This is a proof-of-concept. Several shortcuts were taken that would need to be addressed for production:

- Fixed 2-in-2-out transfers. Every transfer consumes exactly two inputs and produces two outputs. Batching multiple payments into a single transaction would require variable input/output circuits.

- No viewing key revocation. A compromised viewing key permanently leaks transaction history. Key rotation with historical cutoffs would be needed.

- No gas paymaster. The relayer architecture is specified but not implemented. Users currently submit transactions from their own addresses, which leaks identities.

- In-memory Merkle trees. The client rebuilds state from on-chain events on each startup. Persistent local storage with incremental sync would be required for usability at scale.

- Not audited. The circuits, contracts, and client code have not undergone a security review.

None of these are fundamental limitations, each has a known mitigation path. They reflect deliberate scoping decisions to keep the PoC focused on the core privacy and compliance mechanisms.

What Comes Next

The immediate next steps for the PoC are variable input/output circuits for efficient payment batching, a functional gas paymaster for relayed transactions, and persistent client state. Beyond that, the design leaves room for cross-pool transfers between shielded pools on different networks and integration with proof-of-innocence schemes for enhanced compliance posture.

For institutions tokenizing fiat on Ethereum, a gated shielded pool offers payment privacy with a compliance model that maps directly to existing banking practice: identity at onboarding, selective disclosure for auditors, revocable access. The tradeoff is a smaller anonymity set than permissionless alternatives and tooling that is not yet production-grade. But the cryptography is proven, the architecture works end-to-end, and the anonymity set grows with every customer onboarded.

The implementation is open source. The specification covers every circuit constraint, data structure, and security consideration in detail. The use case and approach documents on the IPTF Map provide additional context on how this fits into the broader institutional privacy landscape. Pull requests are welcome.