Building Private Bonds on Ethereum

2025 has been a turning point and an unprecedented wave of tokenization is on the horizon. For those new to the topic, tokenization means representing traditional financial assets (like bonds, stocks, or real estate) as digital tokens on a blockchain. The main standard for tokens on Ethereum is ERC-20, a representation of fungible tokens that is very versatile and can represent any form of asset. This article explores solutions for the problem encountered when using the straight ERC-20 standard. Ethereum being a fully transparent ledger, using ERC-20 exposes too much: who holds what, every transfer, every counterparty relationship. For institutions, that’s a dealbreaker.

This post walks through a proof-of-concept that reconciles tokenization with privacy. We built private zero-coupon bonds using zero-knowledge proofs, achieving confidential balances and transfers while preserving a full audit trail for regulators. We’ll cover why we chose this approach, how the protocol works, and where it falls short.

The full implementation is open source, with a detailed specification of the protocol.

Why Zero-Coupon Bonds?

Zero-coupon bonds are bonds sold at a discount that pay their full face value at maturity, with no periodic interest payments.

A simple example is: Alice buys a bond from Bob for $950 today that will be worth $1,000 in one year. Alice holds the bond until maturity, then redeems it for the full $1,000. The $50 difference is her return, no interest payments needed in between.

Private bonds are one of the use cases documented in the IPTF Map, specifically in the private bonds approach where we’re drawing the foundation of the explored PoC. The Map is the knowledge base we’re building to help institutions navigate privacy on Ethereum. This particular use case emerged from discussions with a major European bank, who laid out their requirements in detail.

When you’re trying to bring privacy to financial products on-chain, you want to start with the simplest possible instrument. Zero-coupon bonds are ideal: no periodic coupon payments, no price feeds from oracles, no daily rebalancing. A single timestamp check is enough to enforce the entire contract.

If we can get this right, the path to more complex instruments becomes clearer. The same primitives that make a zero-coupon bond private can eventually support streaming payments, structured products, and derivatives.

The Problem We’re Solving

A major European bank approached us with specific requirements. They wanted to tokenize bonds, but with constraints that don’t fit the typical DeFi mold:

| What they need | Why |

|---|---|

| Confidential balances | Competitive advantage, regulatory preference |

| Known identities | KYC/AML compliance is non-negotiable |

| Atomic settlement | No counterparty risk on trades |

| Full audit trail | Regulators must be able to reconstruct activity |

| Permissioned access | Institutional-only, controlled participant list |

The adversarial model here is specific: hide balances, nominal prices, and secondary market execution prices from competitors and the public, while remaining fully transparent to regulators. The issuer sees everything. The public sees nothing but opaque hashes.

Why UTXO on EVM?

The obvious problem with Ethereum is that everything is public. Amounts, counterparties, timing: it’s all visible. You can use private mempools to hide pending transactions, but once they land on-chain, the data is there forever.

Encryption alone is insufficient. An encrypted ledger hides the amounts, but prevents the network from validating that the sender actually has the funds they are trying to spend. You’d need to prove that the sender has enough funds without revealing how much they have. That’s where zero-knowledge proofs come in.

The private UTXO model, borrowed from Bitcoin and refined by Zcash, fits naturally here. Instead of account balances, you have discrete notes. Each note is like a coin with a hidden denomination. When you spend a note, you destroy it and create new ones, proving in zero-knowledge that the math adds up.

This approach has been battle-tested on EVM. Railgun has processed billions in private transfers. EY’s Nightfall demonstrated enterprise-grade privacy for supply chain applications. Zcash itself has operated for years with rigorous academic scrutiny. We’re not inventing new cryptography; we’re applying proven patterns to a new use case.

Why not use alternatives?

Fully homomorphic encryption would let you compute on encrypted data directly, but it’s still too slow for production. Trusted execution environments like Intel SGX require hardware trust assumptions, that we wanted to avoid for now. A purpose-built L2 like Aztec is promising, but we wanted to stay on mainnet EVM for composability and familiarity: exploring L2 deployment is the natural next step.

The UTXO approach gives us minimal on-chain footprint. The contract stores only commitments (hashes of notes) and nullifiers (spent-note identifiers). No amounts, no addresses, no linkable metadata. And because we’re running a model where the issuer is a centralized relayer, throughput is limited only by the underlying network’s TPS, not by coordination overhead between decentralized parties.

How It Works

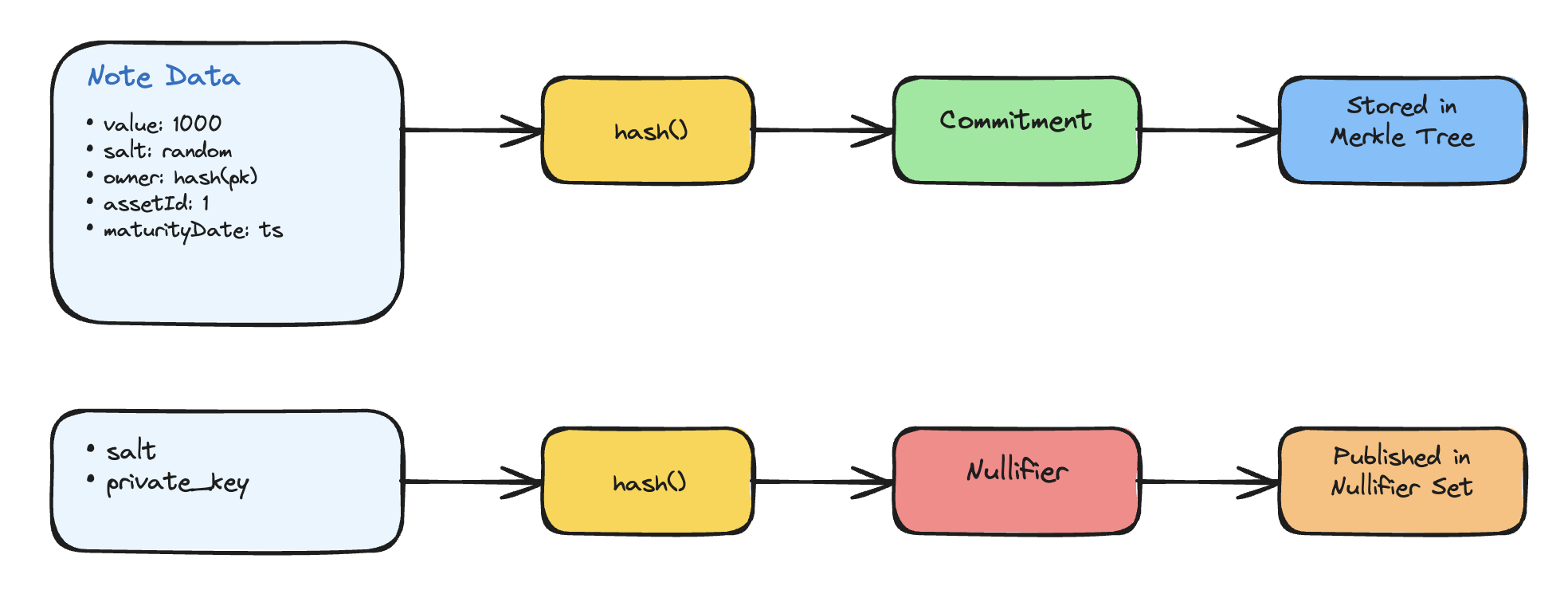

The core data structure is the note. Each note contains:

value: 1000 // Bond denomination

salt: random // Blinding factor for uniqueness

owner: hash(private_key) // Shielded owner identity

assetId: 1 // e.g., US Treasury 2030, ISIN equivalent

maturityDate: 1893456000 // Unix timestamp (2030-01-01)

From this, we derive two values using a SNARK-friendly hash function. The commitment is a hash of all fields, stored in a Merkle tree on-chain. The nullifier is a hash of the salt and private key, published when the note is spent. Anyone can see that a note was spent, but they can’t tell which one or for how much.

Commitment = hash(value, salt, owner, assetId, maturityDate)

Nullifier = hash(salt, private_key)

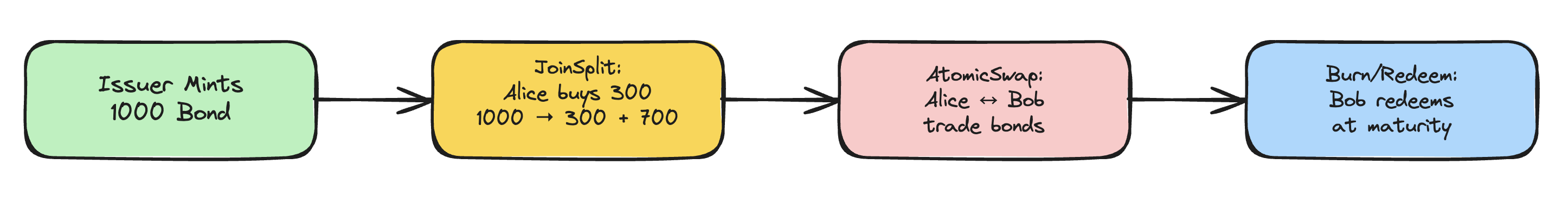

The protocol has four operations.

When an issuer creates a bond tranche–a specific issuance or series of bonds with identical characteristics like maturity date and terms–they generate a note for the full amount and mint its commitment on-chain. No proof is needed here because the issuer is trusted. The Merkle tree grows by one leaf.

When an investor buys bonds, the issuer splits their note. Say they have 1000 and the buyer wants 300. The issuer creates a proof that destroys the 1000-note and creates two new notes: 300 for the buyer, 700 as change. The proof demonstrates that 1000 = 300 + 700 without revealing any of those numbers. This is the classic JoinSplit pattern from Zcash.

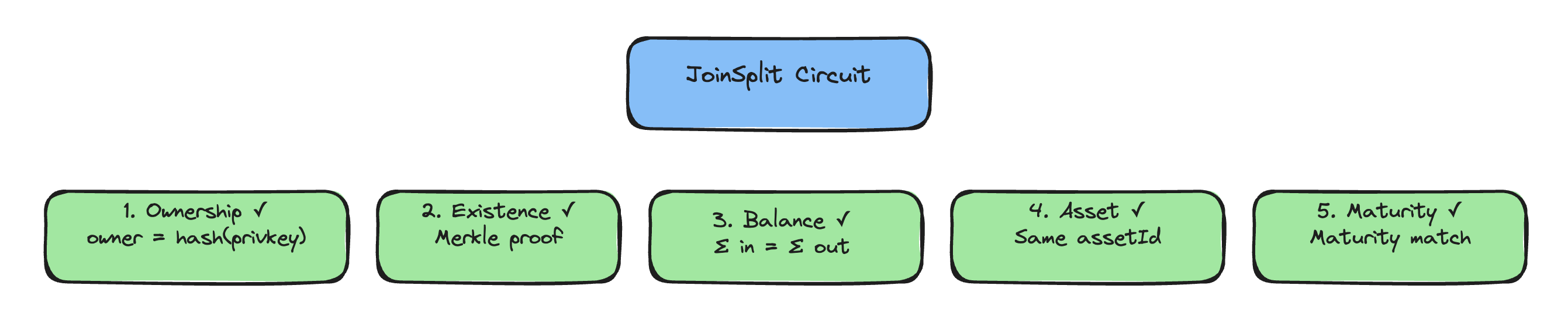

The circuit enforces several constraints:

- Ownership:

owner = hash(private_key). Prover knows the private key - Existence: Input note commitment exists in the Merkle tree (verified via path)

- Balance:

Σ input_values = Σ output_values. Conservation of value - Asset Consistency: All notes use the same

assetId - Maturity Match:

input_maturity = output_maturity. Maturity preserved

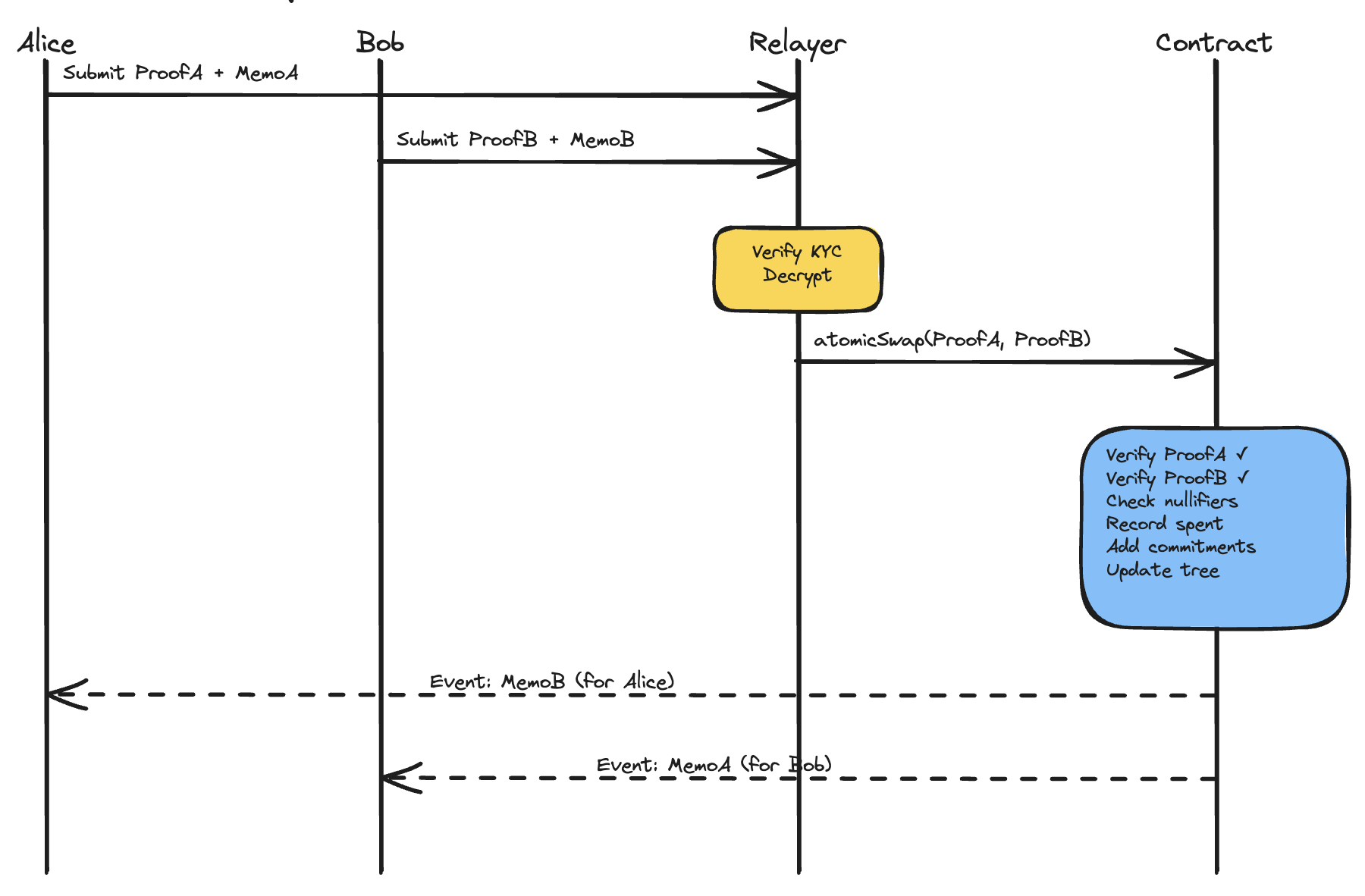

When two parties trade, things get more interesting. Alice wants to swap her bond for Bob’s. They can’t just do two separate transfers because one might fail. Instead, both create proofs that spend their notes and output to the counterparty. The relayer submits both proofs in a single atomicSwap transaction. Either both execute or neither does.

But there’s a coordination problem. After the swap, Bob needs to know the details of his new note (value, salt) to spend it later. The commitment is public, but it’s just a hash.

We solve this with encrypted memos and a two-key model borrowed from Zcash. Each participant has a spending key (to authorize transfers) and a viewing key (to decrypt incoming notes). Alice encrypts her note’s details using ECDH key exchange with Bob’s public viewing key, then runs the shared secret through ChaCha20-Poly1305 (an authenticated encryption algorithm) to produce ciphertext that only Bob can decrypt. Bob does the same for Alice. These encrypted memos are stored on-chain in transaction calldata, ensuring data availability: even if the relayer disappears, participants can recover their transaction history by scanning the chain.

When bonds mature, the holder redeems them. The proof looks like a normal spend, but the output notes have value zero. The contract checks that the current timestamp exceeds the maturity date. Once verified, the nullifier is recorded to prevent double-redemption.

The cash settlement happens off-chain through traditional banking channels. This is the classic Delivery versus Payment (DvP) challenge: the bond settles instantly on-chain, but the cash leg may take T+2 via SWIFT. True atomic settlement would require either a tokenized cash leg (stablecoin or CBDC) or a legal framework ensuring the off-chain payment is binding. For this PoC, we assume the issuer is trusted to honor redemptions, which is standard in institutional bond markets.

The Relayer Model

The issuer acts as a relayer for all transactions. This isn’t a compromise: it’s a feature that institutions and regulators explicitly require.

The privacy model here is asymmetric by design: private from the public, transparent to regulators. Institutions don’t want to hide from oversight. They want to hide from competitors while maintaining full auditability for compliance.

The relayer coordinates the market. All participants are known (KYC’d), so there’s no need for decentralized order matching or trustless discovery. The issuer batches transactions, pays gas, and maintains the audit trail. Note that users could technically bypass the relayer and submit proofs directly to the contract, but they’d lose the coordination benefits and still be visible to the issuer via viewing keys.

The issuer holds viewing keys that allow full transaction graph reconstruction. Regulators get complete visibility when needed, while market participants only see their own transactions. The cryptography protects against external observers and competitors, not against the issuer or regulators.

Here’s what different parties can see:

| Party | What They See |

|---|---|

| Public | Commitments (hashes), nullifiers, Merkle roots |

| Participants | Their own transactions only |

| Issuer | Full transaction graph, all amounts, complete audit trail |

| Regulators | Same as issuer (via compliance framework) |

What We Built

The implementation has three components.

The circuit is written in Noir, Aztec’s domain-specific language for ZK proofs. It compiles to a HONK proof that can be verified on-chain. The JoinSplit logic handles both transfers and redemptions with the same constraint set.

The smart contract is minimal Solidity. It stores commitments in an array, tracks nullifiers in a mapping, and verifies proofs through a generated verifier contract. The Merkle root is recomputed on each update: we chose this approach for code clarity and auditability in a PoC, though production systems would use incremental Merkle trees (as implemented in libraries like Semaphore or zk-kit) to maintain constant-time updates.

The wallet is a Rust CLI that ties everything together. It generates keys, manages notes, constructs proofs, and interacts with the contract. In production, this would be a proper application with key management, but for a PoC, a command-line tool is enough.

Limitations

Nullifier bloat: Every spent note leaves a nullifier on-chain forever. The nullifier set can’t be pruned without breaking double-spend protection. As usage grows, this storage footprint becomes a scaling bottleneck.

State recovery via trial decryption: To find your notes, you must attempt to decrypt every encrypted memo on-chain. There’s no index telling you which notes are yours. This is computationally expensive and gets worse as the system grows.

Wallet complexity: The UTXO model requires purpose-built wallet infrastructure to manage notes, keys, and decryption. You can’t just use MetaMask. Every deployment needs custom tooling.

Where This Goes

With this PoC we’ve demonstrated that this approach is a solid option. But the deeper question is whether this architecture can be generalized. We built a system where the issuer sees everything, which works for a single bank running its own infrastructure. But can we remove that centralized visibility? Can multiple issuers share infrastructure without exposing their flows to each other, while maintaining the same level of auditability and control?

This is where models like Privacy Pools become relevant. Their “proof of innocence” approach lets users prove their funds aren’t tainted without revealing transaction history. Could similar techniques let institutions prove compliance without granting any single party full visibility? Would it be in phase with the current state of regulation? That’s the kind of question we want to help answer.

This approach has its own set of tradeoffs. Our goal remains to document this space as thoroughly as possible, so key institutional decision makers know where to explore.

The UTXO-on-EVM model works, but we had to build our own version from scratch to fit our private bonds use case. ZK-ZK-rollups bring a generalization of this. Aztec and Miden are L2s that both support UTXO and account-based models, offering different execution tradeoffs. Another direction would be FHE-based approaches that could enable computation on encrypted state without the UTXO model’s complexity. Each comes with different trust assumptions, performance characteristics, and composability tradeoffs.

There’s also the question of DeFi integration. Private notes aren’t ERC-20 tokens, but shield/unshield patterns (as Railgun demonstrates) can bridge the gap. This opens institutional capital to DeFi liquidity pools, lending protocols, and other on-chain primitives while preserving privacy for the bulk of holdings.

If you want to explore the code, the repo has everything: circuits, contracts, wallet, and instructions for running the full demo. Pull requests welcome.

Private bonds are no longer a theoretical cryptographic capability; they are an engineering reality. The infrastructure is ready for the first institutional pilots.